|

Numărul 1 / 2006

A FEW BASIC CONSIDERATIONS ON THE IMPORTANCE OF CROSS-BORDER MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS ISSUE WITHIN THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT

Cătălin Ştefan RUSU*

Rezumat: Controlul operatiunilor de concentrare este unul din pilonii politicii concurentiale adoptata de catre Uniunea Europeana. Totusi, trebuie remarcat faptul ca operatiunile de concentrare transfrontaliera a intreprinderilor din Statele Membre ale Uniunii Europene nu constituie singura modalitate prin care amintitele intreprinderi pot penetra noi piete. In aceeasi ordine de idei, un lucru de necontestat este faptul ca mecanismele de control al operatiunilor de concentrare in Uniunea Europeana evolueaza cat se poate de rapid. Prezentul articol intentioneaza sa analizeze cateva din elementele esentiale concentrarii intreprinderilor in Uniunea Europeana, cu o atentie ceva mai mare conferita aspectelor transfrontaliere ale problemei amintite. Fara a avea intentia de a epuiza subiectul, vom oferi remarci relevante privind reglementarile interne din diferite Sate Membre. Mai mult, vom face referiri si la noile acte normative comunitare menite a conferi mai multa eficienta si certitudine juridica operatiunilor de concentrare transfrontaliera in Uniunea Europeana.

Abstract:The control of mergers and acquisitions is one of the pillars of European Union competition policy. However, one should not overlook the fact that cross-border concentration transactions between undertakings from the EU Member States are not the only options for entering new markets. To the same end, one uncontested fact in this respect is that concentrations' control in Europe has evolved rapidly. The contribution at hand aims at providing the basic guidelines and insights on the process of cross-border concentration process between undertakings within the EU. Without attempting to exhaust the topic, we will provide relevant comments on the national merger control regimes of different Member States. Moreover, we will also draw upon the latest community regulations in the field, which are meant to ensure efficiency and legal certainty to the cross-border concentration process within the European Union.

Introduction The control of mergers and acquisitions is one of the pillars of European Union competition policy. Corporate restructuring through mergers and acquisitions is a fact of business life. There is a natural tendency for markets to consolidate through a process of horizontal and vertical integration. However, cross-border mergers and acquisitions are only one of the strategies that companies follow for market penetration in foreign countries. Other well known strategies include exports, franchising, and direct investment via Greenfield etc. Considering the above mentioned, one uncontested fact in this respect is that concentrations' control in Europe has evolved rapidly. In addition to significant changes in the national merger control regimes in Denmark, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Portugal, a new EU Merger Regulation has entered into force on the 1st of May 2004, this measure launching the most far-reaching reform of European merger control since the adoption of the EC Merger Regulation in December 1989. To this end, we can raise the following question: what will the future of European cross-border concentration system look like? The contribution at hand is meant to asses a few basic aspects of this next phase of concentrations of undertakings, with a focus on the cross-border mergers and acquisitions, as crucial aspects of business and economic activity in Europe. Further on, without aiming at exhausting the subject matter, we will attempt to provide insights into problem areas at national level and possible comparisons. Moreover, taking into account the current Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on cross-border mergers of companies with share capital[1], which aims at creating a legal instrument to facilitate cross-border mergers of commercial companies, the contribution will make relevant reference to the main issues arising from the creation and practical application of an appropriate Community legal instrument which will enable all types of companies with share capital to carry out cross-border mergers under the most favorable conditions. The present article aims at providing the basic guidelines and insights on the process of cross-border concentrations between undertakings within the EU and calls for further research which we undertake to pursue.

Possible Definitions and Classifications Before getting to the analytical part of this contribution, it is appropriate to provide a clear definition of what an undertaking is, for the purpose of the European Union Competition Law. The term 'undertaking' was not defined in the Treaty Establishing the European Community as many would have expected. Consequently, this task had to be thus undertaken by the Community Courts and the competition authorities. In the Polypropylene case, the Commission held that the term 'undertaking' was not confined to those entities which possessed legal personality, but covered any entity which was engaged in commercial activity[2]. Further on, in the Höfner case[3], the European Court of Justice held that the term 'undertaking' covers an entity engaged in economic activity regardless of its legal status and the way in which it is financed. To this end, the notion of 'undertaking' was meant to include: corporations, partnerships, individuals, trade associations, the liberal professions, state-owned corporations and co-operatives.[4] However, employees are, for the duration of their employment relationship, part of the undertakings that employ them, and therefore do not themselves constitute undertakings for the purpose of the application of the European Union competition rules[5]. In the same context, one can notice that the definition of a company as provided in Article 48 of the Treaty Establishing the European Community[6] is a wide one, referring to 'legal persons governed by public or private law', but it excludes non-profit-making entities. The exclusion of non-profit-making companies may to some extent be regarded as the commercial focus of the above mentioned legal provisions[7]. Further on, the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on cross-border mergers of companies with share capital defines the notion 'company with share capital' as a company having legal personality, possessing separate assets which alone serve to cover its debts and subject under the national law governing it to conditions concerning guarantees such as are provided for by Council Directive 68/151/EEC[8] for the protection of the interests of members and others. Generally speaking, concentrations between undertakings can be performed through two basic modalities: mergers and acquiring the control over another legal entity. The merger entails the concentration of two or more separate, independent undertakings. The term 'merger' may be used in a broad and in a narrow sense. The broad sense of the term 'merger' basically overlaps with the term 'concentration'. In a broad sense a merger can be defined as any business transaction by which several independent undertakings come under one and the same direct or indirect control[9]. Such common control is in the hands of the shareholders of the acquiring company. This can be achieved through a merger (in the narrow sense), acquisition or a take-over. Most of the times, the decision-makers are satisfied with a corporate control based on shareholding and wish to continue the legal existence of the acquired company. The result of the transaction is thus a group or an enlarged group of companies. In a narrower sense, a merger is a transaction by which one or more participating undertakings cease to exist as separate legal entities, resulting in only one surviving company, which may have been newly founded for that purpose or which may have been one of the participating companies (acquiring or target undertaking). To this end, mergers can be further categorized in mergers by absorption and mergers by establishment[10]. Being an elaborate, complex type of concentration, the merger (as explained in its narrow sense) is not always the first option the undertakings which intend to concentrate might take. This is probably because at least one of the merging entities will cease to exist. Both scenarios (mergers by absorption and mergers by establishment) are referred to as statutory mergers. A statutory merger is often a step or a part of a merger in the broader sense. Acquiring the control over another legal entity entails the fact that one or more legal entities that already have control over at least one undertaking, acquire, in a direct or indirect manner, the control over one or more undertakings and thus exercise a determinative influence over the market behavior of the dominated firm[11]. Basically the acquisition of a company entails the purchase of all its assets or all its shares, by another legal entity. A purchase of an undertaking's shares may be also termed as a take-over. Typically, however, take-overs refer to acquisitions where a listed company is the target and its shareholders are approached through a public take-over bid issued by a bidder who attempts to induce them to sell their shares to him[12]. A more in depth view which eventually approaches the problem of cross-border mergers within the European Union, provides that a merger of undertakings may be defined as a corporate restructuring transaction in which all the assets and liabilities of the acquired company or companies are transferred to an acquiring company, the acquired companies then being dissolved without going into liquidation. Further on, according to this view, there are two types of concentrations:

In the same context, a cross-border concentration is a transaction as mentioned above, involving undertakings at least two of which are governed by the company laws of different states / Member States of the European Union. The definitions of mergers by acquisition and mergers by the formation of a new company as set in Article 1 of the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on cross-border mergers of companies with share capital are taken from Directive 90/434/EEC[13], which also covers aspects regarding mergers between companies from different Member States and forms of company other than public limited liability companies. These definitions are in keeping with those in Directive 78/855/EEC concerning domestic mergers of public limited liability companies[14]. The scope of these definitions include all Community companies with share capital which, in the unanimous view of the Member States, may be typified as companies having legal personality and separate assets which alone serve to cover the company's debts. The meaning of the above mentioned terms is wider than the one provided in Directive 78/855/EEC, not being limited to public limited liability companies, but covering all companies with share capital[15]. The future Directive on cross-border mergers aims to capture transactions where shareholders exchange shares in the transferring companies substantially in return for shares in the merged companies. Any cash consideration for the transaction is limited to a cash payment not exceeding 10% of the nominal value, or in absence of a nominal value, of the accounting par value of those securities or shares[16]. However, the nominal value, or accounting par value, may not be an accurate reflection of the true economic value of the companies involved. This is more likely to be indicated by the market price of the shares, and a limit of 10% may be seen as unnecessarily restrictive of the types of transactions that should properly be caught by the proposal. Thus, it can be argued that a more appropriate solution may be to prescribe the types of transaction by reference to some fraction of the net asset value of the transaction. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions have different consequences with respect to legal obligations, acquisition procedures, and tax liabilities[17]. In a cross-border concentration, the assets and operations of two undertakings belonging to two different economies[18], according to opinions expressed in the doctrine, may be combined to establish a new legal entity. As provided above, in this context the target company may cease to exist as a separate entity. The transaction can be executed through an exchange of stock or assets. Generally, the procedures for executing a concentration transaction tend to be fairly straightforward. Cross-border mergers often require the approval of both the acquiring and target firm's shareholders (depending on the legal norms in force) and the acquiring firm assumes all of the target's assets and liabilities. Cross-border mergers (in the narrow sense of the term) may be further categorized:

Moreover, in a cross-border acquisition, the control of assets and operations is transferred from a local undertaking to an undertaking from a different Member State, the former becoming an 'affiliate' of the latter. Cross-border acquisitions may appear as full (foreign interest of 100 %), majority (foreign interest of 50 to 99 %), and minority (foreign interest of 10 to 49 %) acquisitions. Acquisitions involving less than 10 % are classified as portfolio investment. Cross-border acquisitions can take two forms as well: asset acquisitions and share acquisitions.

As stated above, mergers tend to be rarer and acquisitions dominate cross-border concentrations transactions. Further on, in terms of the relationship of the acquiring and the target companies, cross-border mergers and acquisitions can be classified as horizontal, vertical or conglomerate.

Most cross-border mergers and acquisitions are horizontal, some of them are conglomerate and fewer are vertical; out of these, horizontal cross-border mergers and acquisitions are potentially the most damaging to the competitive process, while the impact of vertical and conglomerate mergers on competition is more controversial, as they can bring about both harmful consequences and improvements upon competition[20]. The concentration deals can be also classified into three main groups, according to the nationality of bidders and targets:

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions may be typified as 'friendly' and 'hostile', as well, depending on the decision of the board of the target company[21]. In a friendly merger or acquisition, the board of a target firm agrees to the transaction. However, a hostile merger or acquisition is undertaken despite the wish of the target firm and the board of the target company rejects the offer. The overwhelming number of cross-border mergers and acquisitions are friendly, while most hostile cross-border mergers and acquisitions occur in the industrial economies. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions may also be characterized as either inward or outward. Inward cross-border mergers and acquisitions incur an inward capital movement through the sale of domestic firms to foreign investors, while outward cross-border mergers and acquisitions incur an outward capital movement through the purchase of all or parts of foreign firms. However, inward and outward cross-border mergers and acquisitions are closely related, since mergers and acquisitions transactions involve both sales and purchases[22]. From a financial point of view, cross-border mergers and acquisitions may be financed in several ways, including foreign direct investment, portfolio equity investments, domestically raised capital and capital raised from international capital markets. On a global scale, most cross-border mergers and acquisitions are financed through foreign direct investment in industrial economies. However, changes in the levels of cross-border mergers and acquisitions are not always reflected in changes in foreign direct investment flows[23].

Brief Historical Approach of the Evolution of the Cross-Border Merger Regulations within the European Context Although the problem of concentrations / mergers (in the broad sense) entails significant consequences for the purpose of the application of the European Union competition policy, one can notice that neither Article 81 (ex-Article 85), nor Article 82 (ex-Article 86) of the Treaty Establishing the European Community made specific mention of mergers. The European Commission attempted to fill this gap as early as 1973 when it proposed a regulation to deal with the matter[24]. Agreement between Member States was not, however, forthcoming, because although they acknowledged the necessity of a merger control mechanism within the European Community at that time, agreement on the specific form of this mechanism could not be reached. After a few failures in adopting a European merger regulation, the European Court of Justice did not remain idle. It signaled, as in the other areas where there has been difficulty in achieving results through the legislative process, that it would use its own power in interpreting the legal norms in force, in order to fill the existing legislative gaps.[25] Further on, on December 14th, 1984 the Commission adopted a proposal for a tenth Council Directive on cross‑border mergers of companies.[26] Several committees of the European Parliament examined the proposal, including the Committee on Legal Affairs, which adopted its report on 21 October 1987.[27] However, the Parliament did not deliver its opinion owing to the difficulties raised by the problem of employee participation in companies' decision‑making bodies. This situation of deadlock lasted more than fifteen years. The uncertainty regarding the need of a merger control mechanism within the Single European Market led to the promulgation in 1989 of Regulation 4064/89[28], most mergers being dealt with, from that moment on, under this new legal device, not excluding though the application of the relevant provisions of the Treaty Establishing the European Community. Although Regulation 4064/89 suffered several amendments, and was finally replaced by Regulation 139/2004[29], the need to regulate the cross-border concentrations' field was still pressing. As early as the completion of the Single European Market at the end of 1992 resulting also in the removal of all barriers to trade, European Union domestic firms faced increased competition in their product markets. Before the establishment of the Single European Market, companies across Europe as well as in the rest of the world prepared themselves to the challenges posed by operating in a more competitive environment. To this end, some companies concentrated their operations, while other companies rationalized their production, and tried to achieve cost synergies and efficiencies by merger. Moreover, many companies strengthened their market position by undertaking cross-border acquisitions.[30] In 2001, against the backdrop of a wholesale withdrawal of proposals which had been pending for several years, the Commission withdrew this first proposal for a tenth Directive with a view to presenting a fresh proposal based on the latest developments in Community law. A resolution of the European Company (Societas Europaea) question having been reached on October 8th, 2001, the work on preparing a new proposal for a Directive on cross‑border company mergers accordingly resumed[31]. In the light of this state of affairs and of the fact that the parties involved have had an opportunity to comment on the broad lines of the above mentioned cross-border mergers and acquisitions proposal, both as part of the consultations carried out by the High‑Level Group of Company Law Experts and as part of those on the Commission Communication to the Council and the European Parliament of the 21st of May, 2003 entitled Modernizing Company Law and Enhancing Corporate Governance in the European Union - A Plan to Move Forward, further consultations, impact assessment, comments and reactions on the present proposal, the speedy adoption of which is wished for by those interested, have been brought up. Since the publication by the Commission of the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on cross-border mergers of companies with share capital on the 18th of November, 2003, consultations with representatives from organizations including National Confederations of Industry, National Financial Services Authorities, Investment Management Associations, the Law Society, the National Stock Exchanges, National Associations of Pension Funds and so on were carried on. All in all, as a follow up to this proposal for a directive, most of these reactions welcome the proposal to facilitate cross-border mergers of companies in different Member States in a cost effective way, whilst also providing appropriate safeguards for existing shareholders and creditors. Further on, the fact that the proposal for the Directive covers small and medium-sized enterprises and also large enterprises, as well as the basic principle that the procedure should be governed in each Member State by the principles and rules applicable to domestic mergers of companies in that Member State, was largely appreciated. Thus, the Member States seem committed to extending the opportunities for corporate restructuring across the European Union as crucial aspects regarding the Single Market. Therefore, it is imperative that the Directive, once agreed, offers practical solutions to the issues of cross-border restructuring for businesses within the European Union, provides legal certainty and avoids unnecessary burdens and constraints on business.

Why Does the European Union Need an Enhanced Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Mechanism? Short Overview of the Scope of the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and Of the Council on Cross‑Border Mergers of Companies with Share Capital The pace of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in the European Union is evidently heating up. In the past, mergers and acquisitions were mostly domestic and friendly. The launch of the Euro and continuing market integration in the European Union will increase the number of cross-border transactions. Since further restructuring in the European Union needs to be facilitated, a clearer framework defining the role of national authorities in that process is needed. Over the past period national authorities have reacted in different ways to announced cross-border mergers and acquisitions; for example, the Portuguese authorities blocked at a certain moment a planned merger between Spanish and a domestic bank. Even in domestic mergers national attitudes vary widely: shareholders and markets are left to decide the course of events (see examples from the United Kingdom and Spain); further on, in France and Italy a regulatory body determined whether a hostile bid for a bank is allowed to go forward. The importance of this issue cannot be sufficiently emphasized for two reasons. The first is that under the provisions of the Treaty Establishing the European Union, acquisitions by other European Union - based entities cannot be subject to discrimination. The second is that the completion of the Single Market requires freedom to invest in any other member country. Unfortunately, the latest practice in the regulation of cross-border mergers and acquisitions does not entirely match these principles. To this end, in several countries, for this reason, there dominated a view providing that the discretionary powers of national authorities to block cross-border deals should be limited to some very specific circumstances. The purpose of the proposed Directive[32] is therefore to fill a significant gap in company law left by the need to facilitate cross‑border mergers of commercial companies without the national laws governing them forming an obstacle. At present, as Community law now stands, such mergers are possible only if the companies wishing to merge are established in certain Member States. In other Member States, the differences between the national laws applicable to each of the companies which intend to merge are such that the companies have to resort to complex and costly legal arrangements. These arrangements often complicate the operation and are not always implemented with all the requisite transparency and legal certainty. They result, moreover, as a rule, in the acquired companies being wound up, which may be a very expensive operation. Thus, there is an increasing need today in the European Union for cooperation between undertakings from different Member States, as there will be tomorrow in the future enlarged Union, not forgetting the EFTA countries[33]. For a number of years now, Community undertakings have been calling for the adoption of a Community legal instrument that meets their needs for cooperation and consolidation between companies from different Member States and that enables them to carry out cross‑border mergers and acquisitions. More than ever, all companies, whether they are public limited liability companies or any other type of company with share capital, desire to have at their disposal a suitable legal instrument enabling them to carry out cross‑border mergers under the most favorable conditions. The costs of such an operation must therefore be reduced, while guaranteeing the requisite legal certainty and enabling as many companies as possible to benefit. In this respect, the scope of the Directive will be drawn in such a way so as to cover above all small and medium‑sized enterprises, which stand to benefit because of their smaller size and lower capitalization compared with large enterprises, and for which, for the same reasons, the European company Statute does not provide a satisfactory solution. Having taken into account the above mentioned and after having briefly passed through the historical aspects of the evolution of the cross-border merger regulations within the European context and then assessing why does the European Union need an enhanced cross-border mergers and acquisitions mechanism, we are able to conclude that the need to adopt an enhanced cross-border concentrations legal device arises as a consequence of recent developments in European company law, namely:

Last but not least, in accordance with the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality as laid down in Article 5 of the Treaty Establishing the European Community[36], the objectives of the proposed action, namely to facilitate mergers between companies from different Member States, cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States acting alone, although consistent efforts for legislative coherent regulations in the field have been made by the Member States, the newly admitted States to the European Union and the applicant States. Each Member State by itself cannot organize the operation in full because cross-border mergers and acquisitions have a dimension which goes beyond national frontiers. These objectives can therefore be achieved only at Community level. The Directive will be therefore confined to the minimum required in order to achieve those objectives and will not go beyond what is necessary to that end.

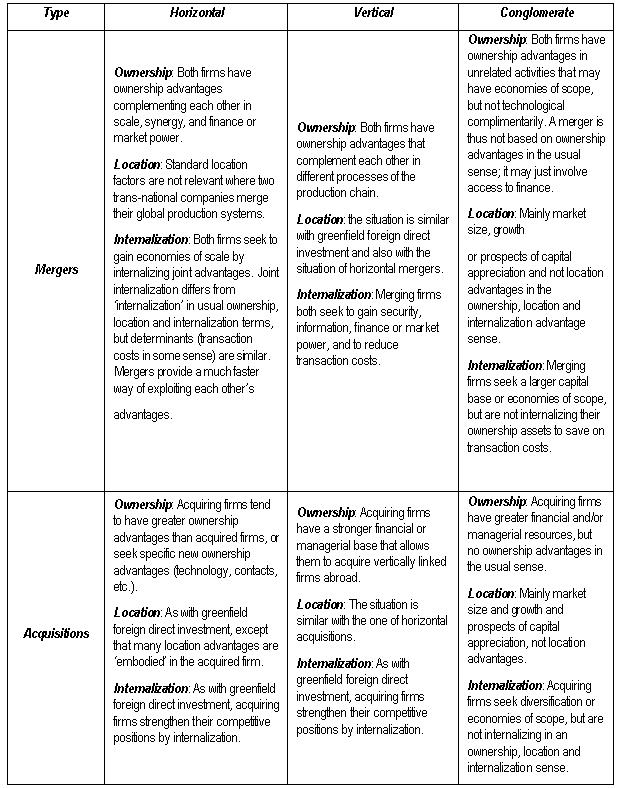

Motivations and Drivers for Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions As stated above, cross-border mergers and acquisitions are one mode of foreign direct investment entry into foreign locations. To better asses motivations for cross-border mergers and acquisitions we will make use of the ownership advantage, location advantage and internalization advantage paradigm / test[37], which is the most influential explanation for production in the context of internationalization and European integration. The test does not explicitly distinguish between different modes of entry and was formulated primarily in reference to greenfield foreign direct investment. However, it does provide a useful theoretical framework to analyze and explain the motives and causes of foreign direct investment through the mode of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. The ownership advantage, location advantage and internalization advantage paradigm / test are applied to cross-border mergers and acquisitions in the following table.

Going beyond this brief analysis provided above, there are some specific factors affecting the motivations for firms to choose cross-border mergers and acquisitions as a vehicle for investment in foreign locations. Among others, speed and access to proprietary assets are particularly important. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions are the fastest means for firms to expand their production and market internationally. When time is vital, takeover of or merger with an existing firm in a new market with an established distribution system is far more preferable to developing a new local distribution and marketing network. For a latecomer to a market or a new field of technology, cross-border mergers and acquisitions can provide a way to catch up rapidly[38]. With the acceleration of European integration, enhanced competition and shorter product life cycles increasingly pressure firms to respond quickly to opportunities in the fast changing economic environment. This is especially highlighted by the fast development and increasing competition in the information and communication technology industry. Accessing proprietary assets is another important motivation for firms to undertake cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Merging with or acquiring an existing company is the least-cost and sometimes the only way to acquire strategic assets, such as research and development or technical know-how, patents, brand names, local permits, licenses and supplier or distribution networks, because they are not available elsewhere in the market and they take time to develop. Such assets may be crucial to increase a firm's income-generating resources and capabilities.[39] Although speed and access to proprietary assets are the main advantages of cross-border mergers and acquisitions, other factors also affect the decision to undertake cross-border mergers and acquisitions:

Firms' motivations are the primary determinant of decisions to undertake cross-border mergers and acquisitions. However, economic changes and regulatory environment may promote and facilitate cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Such changes include technology, the regulatory framework and capital markets. Some undertakings seek to maintain a lead in innovation. In such an environment, one of the quicker ways for them to share innovation costs is through cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Participating firms can gain access to new technological assets and enhance their innovatory capabilities. Such proprietary asset-seeking cross-border mergers and acquisitions from industrial and increasingly from developing economies are becoming a very important form of foreign direct investment. It will become even more common that knowledge-based assets and access to a collective of skilled people and work teams will become more important to competitiveness in an open economy. Within the European Union, the Member States are eager to attract foreign direct investment, not only by removing restrictions, but also through active promotion and by providing high standards of treatment, legal protection and guarantees. Being aware of both the distributional and managerial beneficial effects a cross-border concentration may bring about, the undertakings from the Member States will need a strengthened European regulatory framework, especially through the adoption of an enhanced cross-border mergers and acquisitions mechanism. The practice for dealing with cross-border mergers and acquisitions has also changed over time, on an international scale also. In the APEC member economies, for example, Korea had not allowed foreign purchases of majority interests in local firms before 1998, but in the face of the East Asian financial crisis, it opened nearly all industries to cross-border mergers and acquisitions. In response to the financial crisis, Thailand liberalized its regulatory regime for cross-border mergers and acquisitions and even promoted them. In parallel with investment liberalization, there has been widespread privatization and deregulation, most notably in such service industries as telecommunications, transportation, power generation and financial services. These changes have provided another stimulus to cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Privatization programs in many developing economies and economies in transition have increased the availability of domestic companies for sale. Previously state-owned utility companies, for example, facing new competitive pressures at home, have responded by becoming dynamic international investors. Previously homebound activities, such as water supply, power generation, rail transport, telecommunications, and airport construction, are now undertaken by transnational operators.[41] Cross-border mergers and acquisitions have been facilitated by changes in the capital markets, as well. The liberalization of capital movements, the application of new information technology, more active market intermediaries, and new financial instruments, like the introduction of the Euro, have had a profound impact on cross-border mergers and acquisitions activity worldwide and within the European Union.

Possible Barriers to Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Despite the above strong arguments / motivations for undertakings to concentrate across national boundaries and form enterprises with a European character, there are several possible barriers to the pursuit of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. In this respect, one principal reason might be considered the strategic inertia among the management of European companies. Assessing this issue from a comparative point of view, due to inadequacy or entire absence of strategic planning in European companies, in contrast to American companies, the desirability and possibility of a trans-national concentration remained for a long period of time latent. But this lack of a driving force was certainly not the only reason for not performing cross-border mergers and acquisitions within the European Community.[42] Undertakings from the Member States must have been put off in their wish to pursue cross-border mergers and acquisitions by obstacles such as the lack of sufficient harmonization of the European business environment, despite the progress of the European economic integration. Legal and fiscal difficulties are one set of obstacles for undertakings to concentrate across borders[43]. The lack of a strong and easy to enforce European Union cross-border mergers and acquisitions mechanism constitutes in this respect a serious draw-back for the interested undertakings. As stated above, the European Union does not have such a coherent legal instrument yet. The proposed 10th Directive was not accepted mostly due to controversies regarding employee participation. However, only the 3rd European Community Directive, which contains a common procedure for mergers whereby the assets and liabilities of the acquired undertaking are transferred to the acquiring company, was adopted by all the Member States, except Belgium. Although in some Member States international / cross-border concentrations are theoretically possible, in practice, there were, are and will be too many fiscal and legal obstacles. For example, in countries such as Belgium, France, Italy and Luxembourg, a cross-border concentration will be possible only when a foreign company is absorbed by a domestic one. In case of the opposite, the unanimous consent of the shareholders is required in order to protect national interest against foreign domination and this may be an insurmountable obstacle in practice, when company shares are widely spread.[44] Other legal constrains include statutory provisions to protect the interests of dissenting shareholders[45]. Further on, since supranational structures, such as the European Union, might fear that concentrations will lead to production rationalization and job cuts, as well as a loss of bargaining power regarding management because of the loss of co-determination rights, traditions in European industrial democracy may be considered another obstacle when it comes to cross-border concentrations[46]. Moreover, the legal integration of undertakings from different Member States could be also complicated by fiscal problems, which concern the concentration itself, the further operation of the undertakings and the risk of double taxation as profits or dividends are transferred across borders. Problems as such are less likely to occur when a concentration is performed between two national undertakings within the boundaries of a Member State. However, the above mentioned legal and fiscal barriers can be overcome. Solutions entailing, most of the times, the preservation of the legal identity of the undertakings involved, while formalizing the inter-relationship by financial ties, by joint holding company[47], by a cross-border exchange of shares[48] or by equalization agreements, were often employed. Although the solutions used were not that many, each of the undertakings concerned attempted to adjust them according to their market behavior. Whichever the chosen solution to overcome the legal and fiscal barriers to cross-border concentrations would be, the longing for a coherent cross-border mergers and acquisitions mechanism could be detected in the concerned undertakings' actions. To this end, the European Community appeared to make slow but steady progress starting from the 1960s, towards removing such barriers to cross-border mergers and acquisitions. The preparations for a proposed statute for a European Company started as early as 1959. In July 1970, the Commission had put forward definite proposals for a European Company Statute, the Societas Europaea, meant also to enable companies to merge by giving up their national legal identities and combining into a European enterprise with a legal identity. Under Council Regulation (EC) No 2157/2001 of the 8th of October, 2001 on the Statute for a European Company[49], companies incorporated in different Member States are able to merge or form a holding company or joint subsidiary, while avoiding the legal and practical constraints arising from the existence of different legal systems in different Member States. In the same context draft directives were proposed in order to create a coherent legal instrument meant to facilitate cross-border mergers of commercial companies and to alleviate the most important fiscal problems[50]. Moving on, the different policies adopted by the national authorities in different Member States may be regarded as other obstacles to cross-border concentrations. National political interests can prevent cross-border concentrations. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s most European Governments had assumed an interventionist role in the concentration process at the national level. Moreover, governments have also actively intervened in negotiations with certain concentrating undertakings, in order to keep domestic industries under local control[51].[52] Even later, in the 1980s, period marked by privatization and decentralization, governments occasionally showed a negative attitude towards international / cross-border concentrations[53]. The main reason for this negative attitude of Member States is the fear that international consolidations will be detrimental to the economic or social interest of the state, especially when there are issues regarding key industries at stake[54]. In this context, governments usually seek national rather than cross-border solutions, although, it is often that in fields as such the international consolidation might bring about far more advantages. Further on, governments may consider that a cross-border concentration might lead an undertaking to invest less in the domestic market[55] or that the national industry may prove inferior to its foreign counterpart, resulting in dominance by the foreign company, over the domestic partner[56]. Generally, governments tended to resist concentrations of very large undertakings and high technology undertakings, because of concerns about employment and the fact that they wished to retain the know-how and national prestige. In industries that are not symbols of industrial power, governments tend not to interfere.[57] Leading to rationalization of existing 'plants', with consequential effects on unemployment and regional vitality, the national / regional policies, as described above, may come into conflict with the European Union competition policy, particularly when the latter focuses exclusively on the impact of mergers on competition without taking into account other such factors. Other possible barriers to cross-border mergers and acquisitions, although regarded as minor, could be identified on a case - by - case basis, but usually they are easily overcome. The intensity with which these possible barriers influence the realization of cross-border concentrations differs from situation to situation. However, an eventual corroboration of the above mentioned factors explains why undertakings from the European Union preferred responding to the American challenge and the opportunities provided by the Single Market, by merging with competitors in their own country with whom they shared common legal and tax systems, language, business habits etc. All in all, undertakings that did manage to overcome these barriers and pursued cross-border concentrations were frequently welcomed as the forerunners to European industrial integration[58].

Mergers and Acquisitions in the Context of Different Types of Foreign Direct Investment Having established what motives drive companies to undertake foreign direct investments and what possible barriers they may come across, the question why cross-border mergers and acquisitions would be preferred to other modes of international diversification including greenfield investments needs a complete answer. It is obvious that it is more profitable for undertakings to purchase operating companies intact rather than buy the relevant assets separately and assemble them into an operating company, or "pool" assets with a foreign partner in an allianceship arrangement such as a joint venture. It is less obvious why cross-border mergers and acquisitions should be more profitable than other forms of international diversification, at the margin, or why the popularity of cross-border mergers and acquisitions surged in the 1990s. The cross-border mergers and acquisitions phenomenon ultimately manifests the existence of two 'valuation gaps'. One gap reflects the condition that foreign-owned undertakings are willing to outbid host country investors for host county assets. The second reflects the condition that foreign-owned undertakings find it more profitable to acquire assets through corporate acquisitions than through other modes of international diversification such as greenfield investments or strategic alliances. An understanding of the cross-border mergers and acquisitions process ultimately requires understanding the sources of these two valuation gaps.[59]

Acquisitions v. Greenfield Investments By definition, the acquisition of an operating company in a host country provides the foreign investor with an already assembled collection of assets, including intangible assets such as ongoing relationships with input suppliers and customers. With a greenfield investment, the foreign investor would be obliged to assemble the relevant assets from the very basics. Among other things, the latter activity involves identifying and purchasing the set of relevant assets required to replicate the activities of a similar, but already established, company, as well as creating 'social capital'. The former can be thought of as a network of relationships both inside and outside the foreign affiliate that promotes the coordinated effort of the affiliate's employees and managers to achieve the organization's objectives. Clearly, by acquiring an operating company, foreign investors can avoid significant costs associated with assembling and integrating tangible and intangible assets. Also, acquisitions can usually be accomplished in a shorter space of time than a greenfield investment. For these advantages, investors should be willing to pay a premium to avoid the incremental costs of other modes of international diversification. Therefore, a preference for one mode, in this case cross-border merger or acquisition, arguably reflects the presence of capital market imperfections that contribute to some or all of the cost savings from cross-border mergers and acquisitions being captured by bidders. It is quite plausible that many domestic capital markets are imperfect, at least in the context of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. This is especially likely in countries where mergers often involve private investors, or where securities markets are relatively poorly governed. Variations over time in cross-border mergers and acquisitions might, therefore, reflect changes in capital market conditions that make the pricing of corporate mergers more or less efficient. In this regard, it is frequently argued that merger waves are linked to stock market booms[60]. The general effect of cross-border mergers and acquisitions activities tends to be a re-organization of industrial assets and production structures. This can lead to greater overall efficiency without necessarily significantly greater production capacity. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions facilitate the international movement of capital, technology, goods and services, and the integration of affiliates into global networks. Furthermore, such mergers and acquisitions can bring about efficiency gains through economies of scale and scope. Studies of the performance effects of foreign direct investment, which increasingly consists of mergers and acquisitions, confirm that such concentrations may lead to economy-wide positive benefits particularly as regards improved productivity in host countries[61]. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions can also have positive impacts on growth and employment, particularly if governments have policies which facilitate the associated industrial restructuring. In general, mergers and acquisitions can have the following types of economic consequences from the perspective of host countries as compared to greenfield investments:

Foreign v. Domestic Acquirers Foreign investors are presumed to enjoy certain firm-specific advantages that enable them to overcome a 'liability of foreignness'[62], which includes expenditures associated with understanding and dealing with local political, economic and social conditions about which domestic investors have naturally more knowledge. These firm-specific advantages of foreign undertakings are usually related to their ownership of unique and intangible assets that, in turn, are created by activities such as research and development, engineering, advertising and other sources of intellectual property. The above mentioned advantages enable the foreign undertakings to utilize host country assets more profitably than domestic investors, thereby enabling the former to outbid the latter for host country companies. If foreign investors ordinarily place a higher valuation than do domestic investors on host country assets, it is presumably because the firm-specific advantages enjoyed by foreign-owned acquirers outweigh the associated 'liability of foreignness' that they face in operating host country assets[63]. Domestic policymakers have sometimes used the notion of a valuation gap to justify screening or regulating inward foreign direct investment flows. Several other reasons may also be brought up in order to justify an action as such: the growing importance of intellectual property assets in international competition, the fact that underlying economic changes over the recent past may have accentuated the firm specific advantages of foreign undertakings more generally, and the enhanced ability of foreign solid, competitive undertakings to outbid domestically owned firms for host country companies. The liberalization of tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade may also have lowered the 'liability of foreignness' by better allowing foreign undertakings to engage in vertical and horizontal concentrations. Furthermore, the accompanying increases in domestic competition, associated with the growth of lower-priced imports have undoubtedly been major economic shocks in numerous industries. The technological and policy changes that can alter the valuation gap between foreign and domestic investors could be regarded as examples of real economic shocks that can influence foreign direct investment flows, including cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Summarizing this point of our analysis, the net advantage of cross-border mergers and acquisitions as a mode of foreign direct investment ultimately rests on the existence of capital market imperfections that contribute to a valuation gap between concentrations and other modes of foreign direct investment, including greenfield investments. The willingness of foreign undertakings to outbid domestic investors for host-country companies, in turn, derives from firm-specific advantages that the former enjoy over and above any liabilities of foreignness that they bear. This net advantage might vary over time considering real or financial economic shocks.

The Actors in the Mergers and Acquisitions Markets An analysis of the cross-border mergers and acquisition within the European Union must contain an overview of the categories of actors involved. If we glance at the actors involved in cross-border mergers and acquisition the very influential role of the following must be noted:

Preliminary Issues to Be Considered by the Concentrating Companies Regarding the more technical / practical issues entailed by the completion of a cross-border concentration, one question may arise: how can European Union companies best manage this process? What exactly needs to be carefully taken care of before and during negotiations and before the deal is actually concluded? In order to draw the most benefits out of a cross-border concentration deal, there are several important considerations that undertakings need to take account of:

In sum, there are two fundamental imperatives that must be taken account of in any discussion of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. First, companies engage in a merger or acquisition to create value and that value creation comes about through a combination of synergy realization to cut costs and competitive strategy repositioning to increase revenues and growth. Second, both the synergy realization and competitive strategy goals cannot be achieved without significant attention to the challenge of acquisition integration. If cross-border mergers and acquisitions strategies are to fulfill their potential, and justify the costs companies typically pay to engage in them, managers will need to fully understand and embrace these imperatives.

The Link between Cross-Border Concentrations and Cultural Issues In response to pressures to grow businesses, expand into new markets and access new technologies and opportunities, the last decade has seen an increasing number of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. The cross-border deals are fairly complicated transactions that involve a complex set of variables in order to succeed. Companies looking to acquire or be acquired need to understand far more about each other than just their respective financial positions. The undertakings from different Member States react in different ways to the challenges raised by cross-border concentrations, depending on the defining feature / dimension that best characterize the culture they belong to. Therefore, cross-border cultural issues may explain why certain companies select a certain foreign partner company. Studies have been carried out in order to identify the reasons for choosing a certain business partner. To this end, four dimensions of national culture have been spotted:

Speaking about risks, yet due diligence, in which companies size one another up for the prospective concentration, remains primarily a financial process. This is because it is much easier to get a clear understanding of the company's position with regard to financial, legal or fiscal issues than it is to get a distinct picture of 'soft' issues, such as the company's vision, strategy, organizational culture and people. While harder to pin down, these factors are critical to a deal's success. Due diligence can be though extensive in takeovers of private companies, but is usually more limited when the target is listed. This is because the target's management board must carefully balance the need to disclose information to the bidder against more extensive legal and contractual secrecy obligations, and its fiduciary duties to its shareholders[71]. In this respect, a recent study on experiences with cross-border concentrations examined how executives of undertakings coped with differences in corporate or national cultures, how they managed the integration process and what post-merger challenges they encountered[72]. Cultural fit appears to be the largest common denominator for successful deals, so a key aspect of the soft side of due diligence involves assessing whether the two company cultures will be compatible. Several questions may be raised in this context. Is one culture bureaucratic while the other is entrepreneurial? Are one risk-averse and the other comfortable with high levels of risk? Is one company's decision-making achieved by command versus by consensus at the other? Culture is not just a concern of the acquiring company. The same study revealed that the company being acquired also places a great deal of importance on the culture of the acquirer, as well as how the acquirer interacts with the target. The greater the subtlety and respect exhibited by acquiring companies and the better that company's track record for acquiring highly regarded companies and treating those companies with respect, the more eager companies will be to be acquired by them. The so-called targets may even seek out their own acquisition.[73] In a cross-border deal, it is commonly assumed that the large undertaking takes over the small one, the aggressive company takes over the meek one and those focused on monetary gain usually take over those concerned with doing a good job in unobtrusive ways. Yet the chemistry between the chief executive officers (CEOs) is what clinches the merger or acquisition deal. In many of the successful mergers and acquisitions, a deep and trusting relationship between the CEOs of both involved undertakings was instrumental in the concentration process. Thus, most of the times a cross-border merger or acquisition can be regarded largely as an extension of the relationship between the CEOs of the concentrating companies[74]. Further on, there are a number of factors that improve the likelihood of successful integration of merged companies. The ability to maintain continuous dialogue between the entities is very helpful. In addition, if companies and leadership teams can learn from each other, integration is facilitated. Fostering a new culture that reflects the former cultures of both companies is also important. Finally, continuity of leadership and a fair division of people representing both companies on the new board is likely to speed up the integration process. The extent to which the key managers of the acquired organization remain in place is another key determining factor for the success of the acquisition. Successful acquirers are willing to learn from their acquisitions. Inevitably, the parent company finds change easier and less humbling than the acquired company; however, the more key leaders of the acquired company feel their skills are valued, the more likely they are to remain. The morale of those at the acquired company can be improved by a vote of confidence in its systems. To this end, Dutch companies, for example, seem to exhibit an unusual talent for bringing merging parties together and keeping them there. Perhaps this can be attributed to certain values and norms in Dutch culture, including direct communication, respect for diverse cultures and consensus-oriented management. The Dutch are tough but up-front negotiators, not giving any room to their opponents, but once the deal has been made, and there are no more surprises. As noted by the number of successful Dutch acquisitions, these traits and values contribute well to successful merger or acquisition deals.[75] All in all, the fit of the respective management teams, their leadership style and company cultures, as well as many other factors, should be considered carefully before proceeding with the deal. A strong relationship between the chief executive officers, persistent communication between the companies and mutual respect are particularly important elements to deal success. While a company's people, vision, strategy and culture may be more challenging to assess than its financial position, these factors can make or break the concentration transaction's long-term success and therefore should not be overlooked.

Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions from a Sectional Perspective It seems appropriate, at this point of our analysis, to asses in a retrospective as well as in a perspective manner, the sectional impact that cross-border concentrations has brought and may further bring about. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions are actively taking place across a large number of sectors, manufacturing as well as services. Petroleum, automobiles, pharmaceuticals, banks and telecommunications are examples of industries experiencing some very large cross-border mergers and acquisitions. In the following lines we will try to briefly asses in an exemplificative way the defining features of the cross-border mergers and acquisitions activity in different industries that have been particularly marked in this respect: automobiles, telecommunications, petroleum, and pharmaceutical industries. Recent mergers and acquisitions in the automotive industry are largely driven by a combination of excess capacity, the increasing costs of innovation and technical development, and regulatory changes. The rapid restructuring of the automotive industry has attracted a great deal of attention. The merger between the US company Chrysler and Daimler-Benz of Germany together with other large-scale deals such as Volkswagen's take-over of Rolls Royce, Ford's take-over of Volvo's car division, and the alliance between Renault and Nissan, is evidence of an industry consolidating at an accelerating speed. The merger wave is also affecting all parts of the automotive industry: vehicle companies, component suppliers and retail sectors, and is to a large extent taking place across national borders. Moving on, the telecommunications sector is the best example of how rapid technological developments in combination with regulatory reform both enable and force companies to seek new partners across national and technical borders. The telecommunications market is becoming increasingly complex in terms of products and services as well as actors. The telecommunications market structure has changed dramatically recently. Changing telecommunications structures result from rapid technological changes, but even more so from regulatory reform. The main reasons for the regulatory changes were to improve economic performance, stimulate the diffusion of new services and innovations, and because a number of new technologies made it less and less sustainable to maintain existing monopoly coverage of services intact. Furthermore, market trends and a need for restructuring are driving the increasing number of large-scale deals between companies in the oil and gas industry. Being of fundamental strategic importance to producer countries, the oil industry has gone through various stages of ownership and organizational structures. The current market situation is thus requiring the oil industry to reinvent and restructure itself. However, it is still a quite fragmented market. Today, however, oil companies are forced to look for partners to exploit synergies and access new sources. The deals are sometimes defensive in nature in that, as a result of hard times, there is a need to achieve maximum cost. Last, but not least, the continued drive towards internationalization and consolidation among pharmaceutical companies is more than anything a result of a pressing need to achieve cost savings and speed up innovation. With new entrants in the market, increasing financial needs for research as well as for marketing and distribution, pharmaceutical companies are under pressure to improve their efficiency. To this end, large pharmaceutical companies, in particular, have been seeking partners in order to gather the resources needed for financing research and development for new drugs and products.[76]

Effects of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions From the above paragraphs we can deduce that the consolidation of the European Single Market structure via the process of merger has, allegedly, resulted in the creation of companies that:

There are, however, wider effects of mergers and acquisitions on the companies, industry and the economy. First of all, there are four groups of subjects that are affected by a merger or acquisition. These are:

If the shareholders of the acquired and acquiring firms gain positive abnormal returns post merger, then the merger can be said to have had positive effects on shareholders. There is, however, plenty of evidence that this is not always the case. This is probably why the European Union concentration control system aims at securing more information to the shareholders and encouraging the return profits to shareholders in the form of dividends. However, it is sometimes maintained that one outcome of mergers is the displacement of inefficient management. Thus, merger activity is seen by a part of the doctrine as a form of disciplinary device operated by the market for corporate control. In this perspective, the remaining low mergers and acquisitions activities in some countries including some European Union countries and Japan, is seen as leading to long term negative outcomes, as inefficient management cannot be punished. When talking about the effect of mergers on employment, whenever two companies merge, job losses usually follow whether the rationalization process involves only the elimination of duplicating departments or also the reduction of total production capacity. It is sometimes argued that in terms of overall welfare the negative effects of job losses are counter balanced by efficiency gains. However, even if this is the case, the fact is that the groups who bear the consequences of job losses, the workers and the governments, are not the same as those who benefit from efficiency gains, mainly the relevant firms, their managements and shareholders. The effects on the industry's competitive environment, and through it on the consumers, tend to be top of the agenda on any discussion on concerns over mergers and acquisitions. Traditional antitrust laws, including European law is, indeed, centered on the assessment of the effects of a merger on consumers and on the industry structure. It is considered to be one of the main aims of the antitrust authorities to assess whether a proposed merger can result in a substantial increase of market power on the behalf of the merged entity. Mergers that are likely to result in much increased market power, with all the consequent negative effects for the industry and the consumers, may not be allowed. The impact of cross-border mergers and acquisitions on corporate performance has been controversial[77]. In a large number of cases, mergers and acquisitions have not produced a better performance for the firm as a whole. However, a positive impact can be detected on the performance of companies which are taken over. As we have seen in the previous paragraphs, this result is especially relevant to those host economies experiencing large-scale privatization of state-owned enterprises or that are in financial crisis. In such a situation cross-border mergers and acquisitions can play a positive role in improving the productivity of acquired firms and in promoting economic restructuring of host economies. Moreover, one can notice that a significant role for cross-border mergers and acquisitions is to encourage longer-term corporate reforms, such as operational restructuring and reallocation of assets. Foreign participation through mergers and acquisitions can be more effective in improving efficiency, competitiveness, and corporate governance. Still, deeper research is needed in order to analyze the actual role and impact of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in the restructuring and continued economic development of financially distressed economies[78]. A cross-border merger may also lead to severe problems with respect to the integration of two corporate governance systems. The resulting problems become especially challenging and interesting if the two corporate governance systems are based upon different legal frameworks, cultures or social perceptions,of the countries of the partners concerned. This is one of the reasons why the European Union aims at a uniform application of a coherent set of legal norms. However, the effects that cross-border mergers and acquisitions produce are not only economic, but also social, political and cultural. The fact that many cross-border mergers and acquisitions are infrastructure-related is directly linked to social and political opposition. For example, it can be an important political issue if the ownership of the national telecommunications or electricity or water provider is to switch to foreigners. On the other hand, in industries like the media and entertainment, cross-border mergers and acquisitions may seem to threaten national culture or identity. A large shift of ownership of important enterprises from domestic to foreign hands may be seen as eroding national sovereignty. In the increasingly integrated European economic environment, it is valuable for competition authorities to strengthen cooperation at the national and at the European level in order to respond effectively to cross-border mergers and acquisitions and to the risk of anti-competitive practices of firms. However, for the developing economies, especially economies in transition, cross-border mergers and acquisitions are a relatively new phenomenon; as a result, they have little experience not only in assuming competition laws and policies but also in enforcing such policies to deal with anti-competitive practices of firms relating to cross-border mergers and acquisitions. To this end and in the context of the constant expansion of the European Union, special attention needs to be paid to the policy-level as well as practical situations that might occur in the newly admitted Member States, and moreover to the similar, but probably more complicated issues that will certainly appear within the applicant States.

Concluding Remarks In a globalizing and liberalizing world with rapid technical change, cross-border mergers and acquisitions constitute an essential part of the process of restructuring that undertakings and economies are undergoing all over the world. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions can play a role in revitalizing ailing firms and local economies through restructuring process, acquisition of technology and productivity growth. To this end, in periods of crisis or transition, for example, mergers and acquisitions may be the only way to inject foreign resources and enable economies to adjust to new circumstances. The fact that acquired firms provide an element of inertia may be an advantage to the host economy in that, existing linkages, skills and business practices can be preserved to the extent that they are efficient[79]. Yet, countries have differed widely in their openness to foreign direct investment, including cross-border mergers and acquisitions, and in the benefits they have realized from the ongoing globalization of industry. Government policies and corporate culture caused some countries to be largely closed to foreign acquisitions until recently. The ongoing liberalization of foreign investment regimes indicates that a broader range of countries could realize benefits from cross-border mergers and acquisitions. From the above paragraphs we can deduce that the European Union encourages cross-border consolidation through mergers or acquisitions. Therefore it aims at designing a system which will allow appropriate, straightforward cooperation between undertakings from different Member States. In this respect, the proposed Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on cross-border mergers of companies with share capital seeks to establish a framework for cross-border mergers where such a process was not provided for previously. The need to adopt an enhanced cross-border concentration legal device reveals as a consequence of recent developments in European company law. Thus, the future Directive will provide a useful and easy to employ tool for corporate restructuring within the internal market. However, it is imperative that the Directive, once agreed upon, will offer practical solutions to the issues of cross-border restructuring for businesses within the European Union; also, it must provide legal certainty and avoid unnecessary burdens and constraints on business. Having regard to the above, we believe that the future Directive which will regulate the problem of cross-border concentrations within the European Union is a clear step ahead with regards to the European Union competition environment. We welcome the European Union bodies' efforts, which lasted more than two decades, to adopt a solid, complex set of rules which will encourage the cross-border consolidation of undertakings from different Member States. Therefore, we strongly believe that the reformation on a wide scale of the European merger control system could only bring coherence and stability within the European Union competition policy.